When I was little, my mom used to sit with me right before I went to bed and tell me how God—no, my mom is an ex-religious woman, she most certainly does not believe in God, and yet, in this story—she used to tell me how perfect I am. How God sat down and paid such close attention to all the details of my face. She’d say he made a line, looked at it, said, “Nope,” erased it, and made the line even gentler—your nose, just so—and that is you. Me, with my perfect face.

What about the rest of me? She forgot to mention that something in my wiring was not okay. That I am different, in a world that only pretends—and sometimes doesn’t even bother pretending—to celebrate individuality. That I don’t have a real capacity to be palatable, and that unless I learn that real quick, I am doomed for a life of standing outside the window looking in.

So I’d fall asleep feeling so perfect, not knowing about trust, because the lack of it was yet to be introduced into my life. I just knew peace—that childhood one, where you are perfect because your mom told you so.

When I started this winding road, this curious journey of an intention that I both wanted wholeheartedly and also said to myself like a quiet spell with disbelief: I want to be whole. When I said that, at age 44, at the end of a long day, in my tiny downstairs office, as my life was crumbling and I was packing my things to rush to my kids, when I put that intention into the world—the universe of possibility—I had to start having real conversations with myself. You know, if that’s really what you’re trying, and you’re not saying it just because it’s the cool thing to say—you can’t fake it. You know why? Because you’ll know. And I made a deal, a long time ago, not to lie to myself. And if you are not one who is into fooling yourself, then when you say it to yourself, you have to really ask the real questions you’ve been dancing around for a while.

So when I set the intention of wanting to be whole, the first real question was: well, am I not whole already? I look like I’m whole—I mean, after all, I’m not like a half-person walking around. Well, why the fuck am I not? Am I whole? And I thought to myself, well, the results don’t look like wholeness. The results don’t match what I would expect somebody whole to have in her life. So no—in that case, I am not whole.

And then, another way to look at it: am I broken? Well, how does one know? Am I in pain? Are there things in my life that I think of and feel pain over? And does that pain come to influence my choices? And if so, that is brokenness. And the answer to that was also yes. This pain is a big part of my narrative. That’s a word I’m using now—back then, I just had to admit that pain was a big component of the definition of my many stories of myself, a big part of who I knew myself to be.

So as my logical conclusion that I was, in fact, not whole, then came the next question: was I ever whole? Was there at some point a state of wholeness for me, or did the universe—in fact, God, nature, whatever you want to call it—make an oops with me? Do I actually believe that people are born whole? I do. So, it became a matter of understanding what went wrong. What does whole even look like?

The beauty of this road, the road to yourself, is that you don’t realize you are in a wide valley. You’re asking different questions that seem unrelated, and months later—years later—the valley opens, and you see on the horizon the connection of all your thoughts. Ahhh. It is a breath of fresh air.

As I was sitting there, trying to navigate out of this non-whole person I now found myself to be, I had to wonder: who am I? It’s a question about definition, because that is the only way I have come to understand anything.

When you ask, there has to be a closed circle in which all the words that describe you should fit, and there you have it—that is the whole. Perfect. My job here is done.

So fuck, what are those words? Because clearly, as soon as I have them all, I will be cured. Of the brokenness, of course.

And so I, of course, started a list. Who am I? Well, I remember one of the first things I wrote was “mountain climber,” because I like to climb the mountain that I live next to. “Mother”—that was another word I chose. There were maybe 10–15 words I put down for myself. They were all true.

But then, one day, I came to an obstacle.

As I was hiking, I was wondering: who am I? And more specifically, in the words that are in the circle that is me, should I include the word “patient”? Am I a patient person?

I had to decide what goes into this tight definition of “ME.” There has to be a definition. It’s a zero-one. It has to be inside the line. And inside the circle, there is no way it can be both. None.

And I swear, I was like, well, let me look at the evidence, like data. I put myself on trial: “Am I a patient person?” I was the judge. I was the jury. And I was also the defendant, hoping the verdict would be a yes. Because that is, of course, the right way to be. But all the same, I had to lead with honesty—I promised that to myself…

Well, I’m the most patient teacher. If you don’t know something, I’ll sit with you, I’ll talk about it, and I’ll think with you some more—especially kids, because they just want to know. They’re not resisting knowledge—they’re curious creatures—and for that, I have all the patience in the world. It just takes a minute until it clicks.

But if you’re arguing with me and you’re making no sense, or if you’re just being difficult, I have no patience for that. None. Zero. I guess another way to say it: I don’t suffer fools. I just can’t.

So was it that I was patient, or was it that I was impatient? Because it was inconceivable to me at the time that I could be both. Or neither. Or that I could choose what to be from all the different spectrums that exist within me.

I was not yet living in the world wide web of me—the multi-spectrums of me, the multi-dimensional version of me, an interconnectedness that comes to life in each given moment. I was still trying to be a defined circle, to fit inside the lines (neatly, might I add).

That type of thinking was just beyond me.

And as I ponder those questions, 3rd Grade Keren comes knocking. I don’t know why. I used to not open the door, but now… when these flashes come, I sit and observe. It happens every so often, and every so often when it happens, it stikes me and I wonder, how long have you not thought about this moment? I didn’t even remember remembering it. I am catapulted to these stairs going down to what led to our library—a dark room with low ceilings—to the adjacent computer room, and in front of me is this woman, Michal, my art teacher. I forgot she existed.

We had an art teacher. Her name was Michal. She had a very stern face. Ha—imagine that, a stern art teacher—what a fucking joke. She had tight curls, high cheekbones, and a crooked type of nose that made her look almost like an eagle, but not one that just wants to fly—one that just wants to watch you. Not in a good way.

And she wasn’t mean, but I didn’t like her. I just didn’t. She wasn’t pleasant. There was a lack of kindness about her, like opening a door when the air has a bite and all you want to do is close it back up and go sit next to the heater.

So she was in charge of that room and the art room, and the computer room was right next to the library. It’s a dark and dreary library in the basement—you need to cross it to get to the computer room. This is the same library where they took my 3rd or 4th-grade class to teach us about the Holocaust.

I remember—I don’t know if you’ve ever seen this clip—of matchstick-like humans, lifeless, in piles. They have lost any human image. You can’t call them humans anymore, but they’re supposed to be just like you because… because they’re Jewish. Because they are humans of a certain kind, the same kind that you were fortunate—or unfortunate—enough to be born into. You’re just watching the movie. And they are being shoveled into a grave, a huge hole in the ground, like it’s nothing.

We don’t discuss it afterward. Me and my classmates are just watching these horrors of the unimaginable, and we’re left hanging, in that dark library, which we now have to walk through in order to get to the computer room.

Teacher Michal thought that art was something she could teach my hand to do. And my hands don’t know how to do art—still.

So that’s the space I’m talking about with this art teacher, Michal. We’re sitting there, and she gives us paper. This is like a type of torture I don’t understand, but many people do it. They give you the thing to do—it’s in your hand, and you’re itching to start—but then come the intricate instructions of how to do it, instead of just letting you do the thing.

So she gives us the paper and explains how to color inside the lines. You want to color it all in the same direction, but you also have to do the border first, and there’s this intricate way of doing it. I remember sitting there, wanting to strangle her or just start coloring. The only way out was to let my mind wander so I don’t lose it altogether. I just want to release. I want to take that thing she put in my hand, a coloring paper, and color, not hear a lecture about coloring.

It’s boring. I don’t want to learn how to color inside the lines. What’s the point? Maybe you should teach me that first.

And so she gives us the paper, and I completely ignore everything she just said. I swear to God, I just don’t care about what she said. I don’t care about coloring inside the lines. Why? If I color inside the lines, will my picture be pretty? If it looks exactly the same as everyone else’s, then will it be good? I don’t get it. It’s not that I need to look different; it’s just that it doesn’t matter. Why am I learning a technique for something I don’t give two shits about?

So I color. I just go to town. I do this internal experiment to see if I can do it fast and jerk my hand just enough to touch the edges, like a muscle jump, you know what I mean?

News flash: the experiment is fascinating, but the precision isn’t there. That’s the game I’m playing with myself: can I do it? And I cannot. The lines keep escaping the edge, and just when I think I may have it down, blip, it goes out again…I’m just having a good time.

She walks quietly between the aisles while we’re all creating our art within the lines. And then she stops. Stops dead behind me. You know, have you ever had a teacher stop dead behind you? You can hear her footsteps, and all of a sudden, they stop, and you can feel her wrath over your shoulder. You can feel her stare; you can feel all the things you’ve ever done wrong in your life.

She stops, dead, and looks at me in disbelief. Like, I know you’re not that thick. I know I just went over this. What the fuck are you doing?

I look at her. There’s so much we exchange without ever uttering a sound. I just look at her, not in defiance, but I don’t know what to say. And finally, she speaks:

“What is this?”

I said, “I was coloring.” There is, and has always been something about the simplicity of my answers that makes people feel like I’m making fun, or joking, or both. And perhaps it is because of the absurdity of what’s going on. She gets mad.

And then she does something that, both in real time and in retrospect, I can’t believe she did. She calls attention to the entire class and says,

“Guys, I just want you to see what Keren did here.”

She holds up my paper for all the kids to see.

“This. This is what it should NOT look like. Remember when I told you what it’s not supposed to look like? This is it.”

She stands above me, holding up the messy paper, and I can see it. The piece of messy paper she’s holding, it is no longer a fun experiment, it is a poor attempt at… what? Art? – don’t make me laugh. And the kids look from the paper to me and back. And I am in utter amazement in that moment.

All eyes are on me, and it’s shameful. There’s no denying it. I can see what they see—the utter mess I created. You can’t deny that when somebody singles you out for being the example of what’s wrong in the world, it hurts. It doesn’t feel good to be the example of what not to be.

But as all my classmates are looking at me, I’m also looking at them. Like, you guys, did anybody tell you why to do it? I don’t get it. What’s the value? I’m asking them with my eyes: can anybody tell me why this is wrong? Look around. Why is it wrong? Because the teacher told you it’s wrong? What?

So they’re looking at me, and I’m ashamed, but I’m also looking at them like, guys, somebody tell me the secret. What’s the secret here? Why is it wrong?

But I’m also thinking to myself: Wow, teacher Michal, you couldn’t resist doing the worst thing that’s been done here. Shame me in front of my class, call me out for doing something when I was supposedly trying to learn it. It bothered you that I didn’t care, so you wanted to punish me?

And to this day, I am not sad about the obvious—the fact that I was shamed. I am sad because somebody cared more about her version of art than she cared about the person, that little girl sitting in front of her, not just shaming me, but also shaming the very expression of creativity she was supposed to teach. She betrayed it all, for what, a momentary power trip – did it feel good?

For me, this memory never became bad about me, because I still don’t know to this day why it’s so important to color inside the lines.

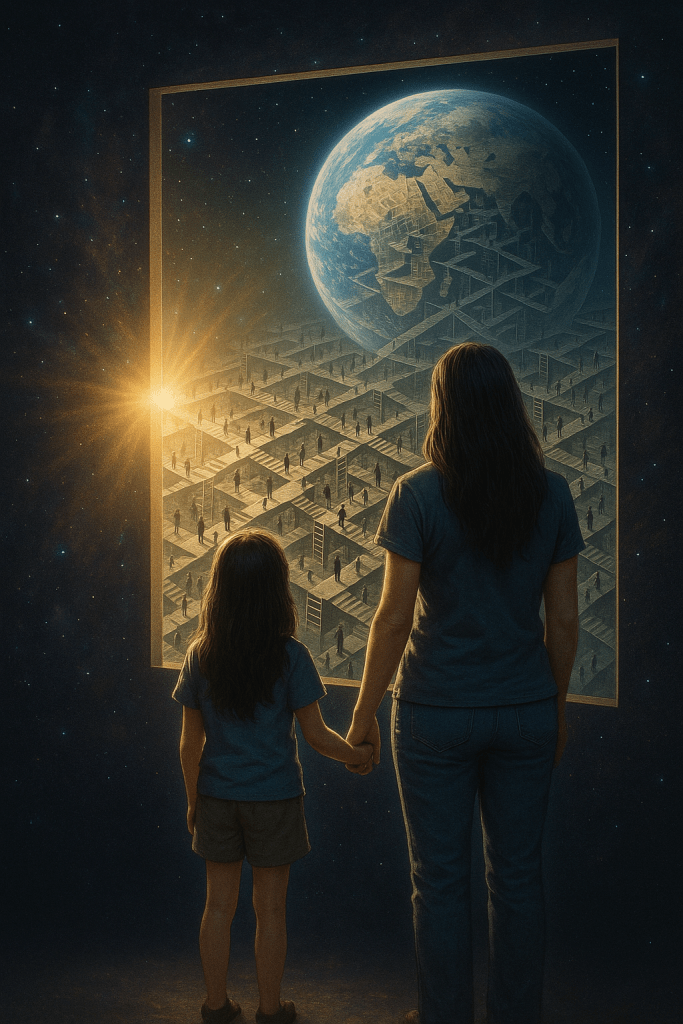

But I remember the sensation. No, I didn’t think I was wrong for coloring outside the lines. It was as if there was a wall, a window, a veil between me and the other kids in the class. I was standing outside. They could all see me, and I could see them. And just as they couldn’t understand why I didn’t follow the instructions, I couldn’t understand why they did.

We all knew that had I tried, I would have been able to—that wasn’t the question. We just now knew: I am standing outside. Thank you, Michal for exposing me to my classmates. For making it known that I am an outsider.

And then, another memory flashes in. There must have been a need to give Michal more to do so she could work full-time, because she was also the “computer room supervisor.” She was in charge of turning them on—I’m resisting making all sorts of snarky comments.

We had these tiny little computers lined up in a U-shape. As far as I remember, they had two games. One of them was the lemonade stand game.

It went like this: A hot summer day appears in green Hebrew letters on a black screen. You’re told it costs X shekels to make lemonade, and you’ll earn X shekels if you sell it. Do you want to do it?

You’re in second, maybe third grade. No paper to actually do math on, so you just think, sure, why not. You press yes. And tada—you win. Wow. My mom was right. I’m a genius.

So you try again. The scenario changes a little, and you think, okay, what if I press no? You press no, and you lose.

After a couple of rounds, I realized the scenarios didn’t matter. It’s a zero-sum game. You say yes, you win. You say no, you lose. That’s it. There’s no thinking.

Once I figured that out, I lost all interest. Of course.

But then I’m looking around the room, and other kids are still playing. There weren’t enough computers for everybody, so we had to take turns. And I couldn’t understand why the other kids still cared about playing the game.

I couldn’t fathom why they hadn’t figured it out yet. Is it possible that an entire class has not figured something so simple out yet. How had they not seen the obvious zero-sum pattern? You press yes, you win. You press no, you lose. How can it be?

So I turned to my friend next to me and said, “Did you figure out the game?”

She looked at me like I was arrogant. Maybe I was. Maybe I am. I don’t know. And she said, “Of course.”

“Of course?” I was shocked. Because I too had a 0-1 – zero = you didn’t figure it out so you are still playing. 1= you figured it out, and now you are done. So why are you still playing? That’s what I asked her. I was baffled. It didn’t make sense.

That’s when she revealed to me the layer of absurdity that I hadn’t even imagined. She said, “Well, what is there to do otherwise?”

Ah. So playing a game that means absolutely nothing was actually better than doing nothing.

And as I looked around the room, I realized I was the only kid in my class who preferred nothing to actively doing nothing.

They had figured out the game. They knew it was pointless. But they were still pressing “yes.” No! They weren’t pressing “no,” even though it was completely pointless. They still wanted to win. Why? Because it was called a game? And a game is better than what? Life? Connection? Or even nothing?

No, seriously—why were they playing? What if we all turned around and looked at each other and said, “Hey, want to play hide and seek?” Well, teacher Michal would get mad.

What if we just talked to one another? What if we all said, “Fuck, what is this? What is this stupidity?”

It was in that moment that I realized something is not right. I am outside the window, looking in, and it’s clear. All I’d need to do to step in the window is pretend to enjoy the win, take my turn—but I cannot. I cannot pretend like that. If the game is meaningless, I don’t want to play.

I stand in solitude outside the window, looking in, and wondering: This is the wiring behind that “perfect face” that God constructed so carefully.

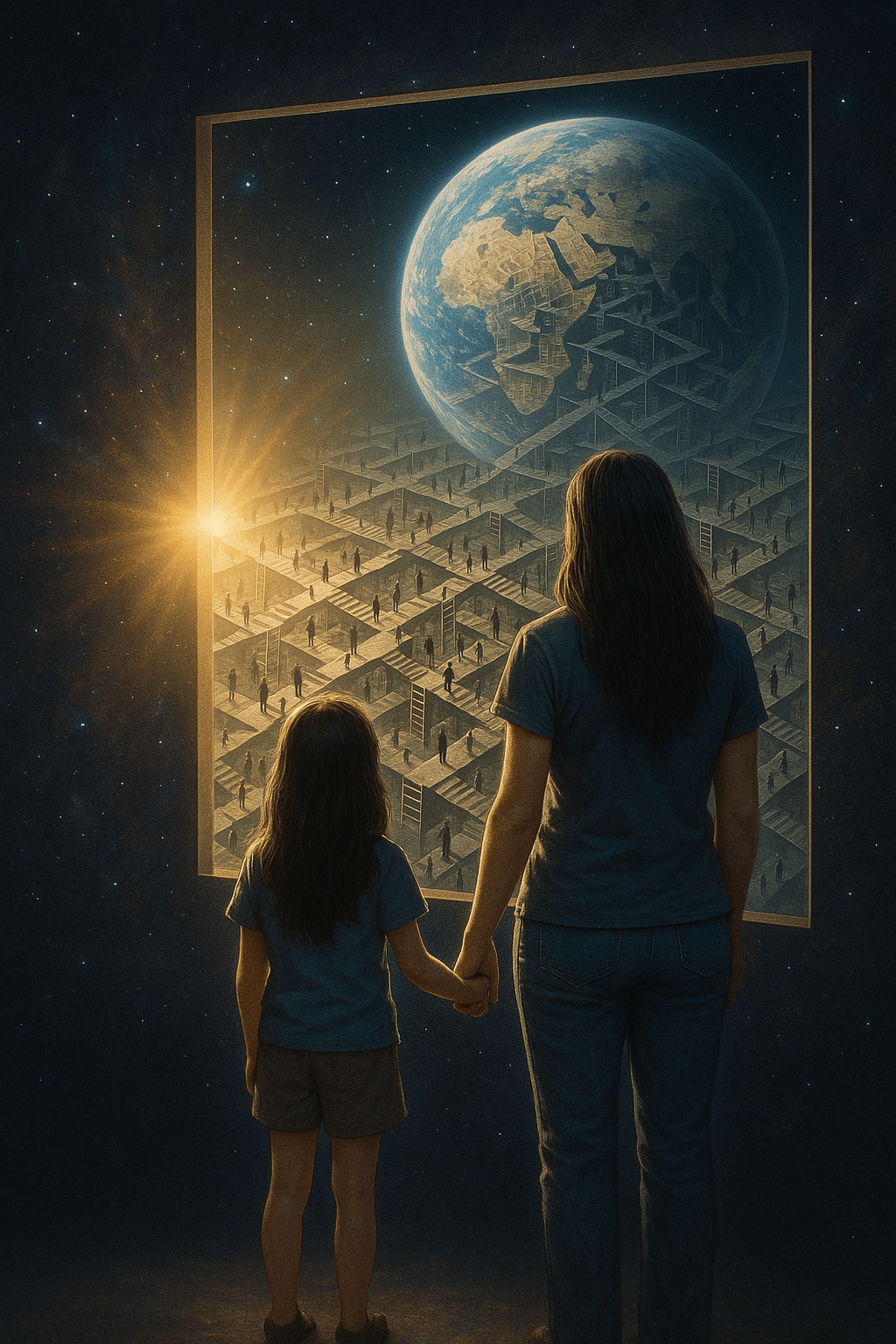

As I stand there in that computer room, in that classroom, with the fluorescent light so low, both being my older self and seeing the world through my younger version, I remember these sensations. I know them well, the disorienting lonely feeling, where the fact that you don’t understand is your wall, your solitude. And once again, I stand there with my younger self, and we are both looking through that impenetrable window. I hold her hand, and we are looking together.

So here I am—Hineni—messy me. I still can’t color inside the lines. Yes, I am patient. And yes, I don’t suffer fools. Yes, I am a paradox, even to myself. Yes, I don’t fit in—not to any line, not to any box. I am not a circle. I am without lines.

And being without lines, you realize you are standing outside a window of neatly shaped lines—a world of shapes and definitions. The very way we communicate—words—is a bunch of definitions in an otherwise definitionless world. Fluid world. A world of wonderment – that has been neatly put into lines we can all walk safely in.

Here I am—outside the window, looking in. Seeing. Wondering, and hoping there are others like me. Standing outside the window. Echoing into the void…

Is there anybody out there?

Leave a reply to batelwien Cancel reply